As Guy Borenstein gears up for Stuller’s Bench Jeweler Workshop in March, there’s one hot topic that will be addressed for the fifth consecutive year: synthetic diamonds.

There’s no shortage of available equipment to detect lab-grown diamonds. According to the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), there are about 40 instruments on the market that aim to discover natural versus synthetic diamonds.

“Five years ago, I asked attendees how many were screening for lab-grown diamonds [LGDs] and one hand went up,” says the director of gemstone procurement for the Lafayette, Louisiana-based manufacturer. That number has grown as the years passed, but “the majority are still not checking,” he adds.

Considering the recent number of undisclosed synthetics sent to labs, retailers should be more vigilant. In the last two months, four labs — comprising one in Italy and three, including the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), with US outposts — have reported incidents of synthetic diamonds submitted for grading under the guise of being natural. The labs, with their multitude of testing instruments and scientific savvy, have the manpower and resources to uncover the truth, but what about retailers, small manufacturers, and dealers? Other than sending every diamond purchased either over the counter or from a jewelry maker to a lab, what can the rest of industry do to guard against unknowing purchases of synthetic diamonds? Screen, baby, screen.

Marc Altman of B&E Jewelers in Southampton, Pennsylvania., started selling synthetics only last year, but has encountered them in newly manufactured goods sold to him as natural and in the engagement rings of unknowing clients. In the case of the new jewelry, he suspects it was an honest error.

“It was one ring,” he says. “It was a big order, and my assumption was that they also made jewelry with LGDs.”

Thanks to his GIA ID100 screening tool, he was able to spot-check trays of new finished jewelry. In the case of individual client rings, he’ll use a polariscope and the ID100 to determine if a diamond is natural or synthetic. In the last three weeks, he’s taken in two rings for resizing that were set with lab-grown and not the natural diamonds that clients thought they had. These examples are why screening goods on intake is critical and reveals deficiencies in disclosure by others at the time of sale. These are lawsuits in the making.

“If I didn’t [screen], my reputation would be at risk,” he says.

Fraud or flub?

Recent high-profile lab incidents aside — like the 6-carat synthetic laser-inscribed as a natural the International Gemological Institute (IGI) examined, or the pink, yellow and brown lab-grown diamonds posing as natural that Gem Science Laboratory (GSI) received — not every facility sees the spike in undisclosed synthetics as deliberate by fraudsters.

As a percentage of all diamonds examined, the number submitted as natural that turn out to be lab-grown is miniscule, says IGI CEO Tehmasp Printer.

“Ten years ago, 95% of parcels were contaminated,” he continues. “Today that number is reduced to half a percent. Initially, some did try to push LGDs as naturals and then labs learned how to ID the material. Now, there are mistakes and errors, but most are not intentional. No manufacturers are polishing LGDs and naturals in the same space; it’s done separately. The problems occur when parcels are given out for memo, and then there is a little switch here and there by mistake.”

Other incidents aren’t as clear. A recent GSI discovery involved mounted brown diamonds with linear graining and polished surfaces “to try to pass it as natural,” maintains Debbie Azar, cofounder and president of GSI. “While initial gemological observations would suggest they were likely natural, our advanced testing processes revealed they were CVD [chemical vapor deposition lab-grown diamonds] almost immediately by looking at their optical defects.”

No matter the intention behind the incidents, GIA takes each one — and steps to avoid them — seriously. For example, nearly every synthetic diamond that comes in for a report is inscribed as such. It also recently unveiled a same-day service for report confirmation of GIA-graded diamonds with or without markings. The service is offered to combat fraudulent inscriptions and for now is free.

“We should all be doing everything possible to ensure consumer trust,” says Pritesh Patel, GIA senior vice president and chief operating officer. Patel is responsible for lab operations. “One is not more vulnerable than another in the trade; everybody should be vigilant,” he cautions.

One of the toughest tasks in effectively screening jewelry today is the large quantity of small stones. The labs can handle it, but it’s tedious.

“Our biggest challenge is testing items encrusted with micro-pavé — jewelry set with 0.005-carat and smaller diamonds,” says Angelo Palmieri, president of GCAL by Sarine. “The challenge predominantly revolves around exercising patience.”

Then there are the hidden halos of diamonds; only visible diamonds can be easily checked on finished jewelry, so the trade must remember to flip pieces on their sides for inspection.

“We see as many naturals in LGD-set jewelry as we see LGDs in natural diamond jewelry,” adds Palmieri. “We see this happen with everybody, from high-end brands to sightholders. We’re not seeing 50% wrong — we see cases where one is natural or LGD. It doesn’t look intentional; it looks like it’s hard to keep track of the melee.”

Azar, too, is familiar with this wearisome process.

“Pieces with smaller diamonds and melee can be extremely time-consuming and the work is intricate,” she says. “We screen thousands of diamonds each day and we are detecting undisclosed laboratory-grown diamonds every day. They are usually in mounted goods where the mounting obscures full observation of the diamond.”

The solution? Enhanced quality controls such as constant and repeated testing when diamonds are loose and once they’re set. “Most companies don’t want to put in the hard work (and patience) that comes with thorough and complete testing,” observes Palmieri.

Like Altman, other retailers can use a microscope, polariscope and GIA’s ID100 in store — they’re compact and not too cost prohibitive.

Labs have myriad methods, including custom machines and proprietary research, to uncover the truth. There are also common methods used by all labs, like “Raman and photoluminescence spectroscopy” and “basic gemological testing,” among others, notes Palmieri.

GIA even has a facility in New Jersey devoted solely to the study of lab-grown diamonds to stay ahead of their developments. “GIA spends a tremendous amount on research,” notes Patel.

Lab consensus is that one instrument isn’t enough. Multiple tools and experienced operators are necessary to reveal undisclosed synthetics.

“Each instrument has its own advantages and limitations,” says Palmieri. “No one machine can give you all the answers.”

Azar urges the trade to adopt a deductive process for distinguishing between naturals and synthetics. For example, does it have garnet crystals? Then it is “definitively natural,” she says. But if a diamond has no inclusions or is type IIa, send it to a lab for testing. For mounted goods, “all bets are off because of the complexities,” she adds.

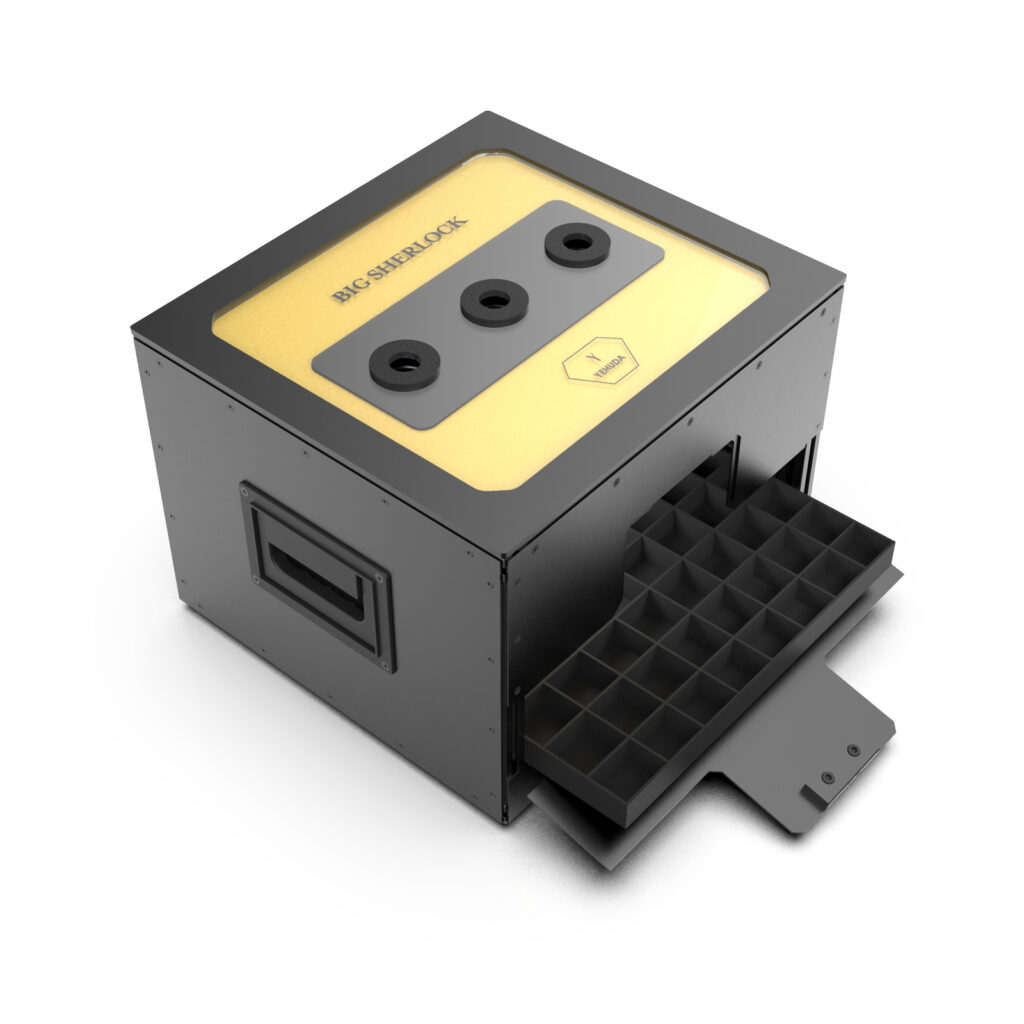

Dror Yehuda, president of Yehuda Diamond Company — formerly a maker of clarity-enhanced diamonds — shifted to manufacturing diamond detectors around 2015. That’s the year, he maintains, that lab-grown diamonds came to market with gusto. “The vast majority of my customers stopped carrying my Yehuda diamonds and moved to LGDs,” he reveals.

As a result, Yehuda built the first Sherlock Holmes detector, which is in its fourth generation. Three models now exist to accommodate a variety of needs and budgets.

To date, he has sold over 15,000 detectors worldwide.

“The second generation was tested by project Assure and was the only detector other than [De Beers’] SynthDetect that detected 100% of the LGDs,” says Yehuda.

The Assure Directory from the NDC is a resource for anyone trying to determine what instruments to purchase. Assure provides results of independent testing of a “wide range of diamond-verification instruments,” according to Samantha Sibley, technical educator at De Beers Group Ignite in the UK, which spearheads De Beers’ corporate approach to innovation.

Assure tests instruments for “diamond accuracy, referral rates, speed, and natural false positive rates [i.e., does the instrument pass any synthetic diamonds as natural?],” she continues. “The latter is the most crucial measure, and all De Beers verification instruments have a 0% false positive rate from both Assure 1.0 [2019] and Assure 2.0 [2022].”

Manufacturing house Stuller takes extreme precautions to safeguard against undisclosed synthetics. The firm has 62 pieces of screening equipment and 40 associates to run them. It even has an in-house GIA lab for melee analysis (Stuller staffers aren’t even allowed inside).

Starting at a quarter of a point, Stuller tests every diamond individually, screening more than 5 million units a year. Each stone is tested by at least two different technologies so one “can compensate for the weakness of another,” adds Borenstein. “In a year, 50,000 units out of 5 million go to the lab for further tests.”

The onus is on Stuller to test because of Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulations.

“Every player throughout the supply chain should test,” he urges. “We are still catching undisclosed stones on a daily basis, so just imagine how many of those are filtering into the market in an area with no screening at all.”

Jay Seiler of Jay Seiler Jewelers in Duluth, Minnesota, is a risk taker. He has a Presidium tester to weed out cubic zirconia and moissanite when he buys gold, but no other equipment in-house to test diamonds. Why? He’s a private jeweler now after years of operating a big store. His clients are largely older, known to him, bought diamonds before the advent of lab-grown, and 90% of his work is custom. Still, what about the new diamonds he buys? Therein lies the risk.

By the time someone faces an undisclosed synthetic, however, it’s likely too late. “You won’t be able to defend yourself in court,” says Borenstein.

“Disclosure is not as explicit as it should be, and that will be a huge challenge for retailers in a few years,” says Palmieri.

Source: DCLA