The company’s synthetics brand, Lightbox, applies post-growth enhancements to its colored lab-grown diamonds, it confirmed with Rapaport News. However, it doesn’t need to tell consumers, because the processes don’t affect the value, and are just one more step in a man-made technological process, a spokesperson argued.

“Our colored (pink and blue) stones are manufactured by a combination of modifications to the synthesis conditions and treatments after synthesis,” Sally Morrison, chief marketing officer at Lightbox, wrote in an email to Rapaport News last week. “Lab-grown diamonds are a manufactured product, and as such it really doesn’t matter how many stages there are to the overall manufacturing process, or whether these comprise separate stages of synthesis and post-synthesis treatment.”

The company also has no problem with the wider lab-grown trade treating diamonds without disclosure, though Lightbox doesn’t enhance its own white stones. Those items come out of its presses with good-enough color, enabling it to keep the cost down by avoiding an extra manufacturing phase. Many other producers do improve the color of their white stones through processes such as High Pressure-High Temperature (HPHT). Morrison refused to specify which enhancement methods Lightbox used.

“All HPHT treatments really do is add cost and complexity to the manufacturing process,” Morrison noted. “This may in part explain why some other lab-grown-diamond manufacturers charge higher prices than Lightbox.”

Still, the production cost is roughly the same for Lightbox’s white, blue and pink stones, despite the extra stages involved in the latter two colors, Morrison noted. That’s one of the reasons the company sells everything at $800 per carat, rather than charging more for colored stones, she said.

Full transparency?

De Beers’ stance on disclosure places the company as an outlier in the debate on whether such transparency is necessary in the lab-grown sector.

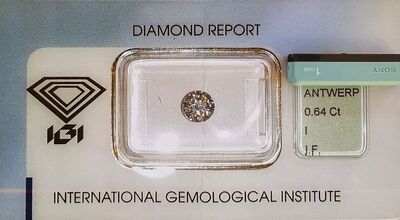

The US Federal Trade Commission’s jewelry guidelines, which instruct businesses how to market diamonds fairly to consumers, give three circumstances in which sellers must disclose treatments to natural or synthetic stones: If the process is not permanent, requires special care, or has a significant effect on the stone’s value. The first two do not apply to color treatments to lab-grown diamonds, but the third might.

“In my opinion, since post-growth treatments are typically done to make the laboratory-grown diamonds marketable, that triggers the third prong of treatment disclosure,” noted Sara Yood, senior counsel at the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, which advises the trade on legal matters.

The issue is important for the industry as the synthetics market is full of white stones with undisclosed treatments, according to Ben Hakman, a consultant on lab-grown diamonds at New York-based Diamond DNA Solutions. The largest producers, mainly in India, pump out brownish goods intended as whites, and then treat them for color.

“The consumer is supposed to know about it,” Hakman said, arguing that disclosure standards should apply equally to natural and synthetic stones. “What does it have to do with…[it] being a lab-grown diamond? You’re justifying treating something without disclosure, and that makes Lightbox no different from all the other guys.”

In certain categories, consumers will pay about 10% more for untreated white synthetics than enhanced lab-growns with the same characteristics, Hakman reported.

“There is a premium [on untreated], but the thing is, they just fly off the shelf,” Hakman said. “In fancy shapes up to 1.99 carats and rounds from 1.30 to 1.99 carats, the untreated goods sell the day they arrive on the market.”

Pinks are slightly different: It’s almost impossible to create them in a machine without further treatments, so “as-grown” goods barely exist, explained Tamazi Khikhinashvili, president of Russian synthetics maker New Diamond Technology. Yet, full transparency is essential for all colors, he asserted.

“It’s very important for the buyer that people know what they’re buying,” he noted.

Source: diamonds.net